A record of the Altwasser family's sailing experiences in their yacht Bingo

Posted

by Richard at 5:10 PM

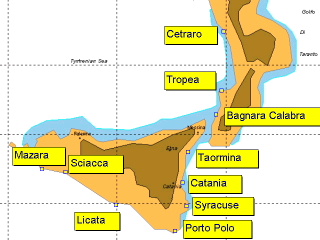

Mazara del Vallo, Sicily to Cetraro, Calabria. August 5th to 18th 2004, 315 miles.

Return to Mazaro del Vallo August 5th – 6th 2004.

After Islam jumped north across the Gibraltar straits and spread west, Mazara became the first Sicilian Saracen foothold in the 8th century. A quarter millennium later, the Normans under Count Roger returned Sicily to Christendom and founded the first Norman parliament in Mazara. The town’s strategic position on an estuary at the south west corner of Sicily is employed today by the island’s largest trawler fleet to fish the shallow Sicilian straits as far as Tunisia and Libya. Mazara’s most famous catch, a life size bronze figure, dancing in a whirling trance, was trawled from the sea-bed between Isola Pantelleria and Tunisia in 1998. This 4th century BC Greek satyr, now displayed in its own museum, links lively bustling modern Mazara with its Hellenic past. Roman and Byzantine remains can also be seen in the Norman Duomo behind which lies a warren of narrow streets, the old Arabic Kasbah, which once again houses a Tunisian community.

Mazara and a few other ports around the Med. occasionally experience the Marrobio a tidal wave that can quickly raise the water level by a meter, recede in a few minutes and repeat this cycle for a few hours. Warning signs around the harbour alert pedestrians to the danger of freak waves suddenly rising from within the harbour and flooding the surrounding pavements. We had left Bingo on July 1st, secured to minimise the potential effects of this tidal oddity.

After five weeks in the UK, visiting friends and family, a glut of TV sport: Euro 2004, Wimbledon, Lords and Edgebaston, we locked our Bristol front door at 7 am, crossed the park and 19 hours later were welcomed by Giovani, Mazara yacht club’s youthful director, with the offer of a drink and invitation to join his party. Bingo was undamaged and dry with a hull waterline displaying a skirt of colourful weed that was visible at 2 am.

On Friday we provisioned and cleaned the boat, gave our phone its fifth national identity, anchored outside the harbour and swimming in the clear refreshing water started gardening the hull with a stiff brush.

Mazara to Sciacca. Saturday 7th August. 25 miles.

The Greeks were first to recognise the healing powers of the volcanic thermal springs and vapours just east of Sciacca harbour. They carved seats in the rock and etched into the stone the names of various ailments that could be cured by each seat. A 20th century building on the eastern cliffs allows modern visitors to take the waters.

Having discovered a fuel air leak, that rendered the engine prone to stop unannounced and a depth sounder that generated random numbers suitable for bingo, we approached the shallows east of Sciacca with care, one person at the bow looking for rocks. The plan was to drop anchor, enjoy the warm waters, continue to attack the accumulated aquatic agriculture and enter Sciacca harbour at the end of the afternoon.

Aurelia aureta, Cyanea lamarckii and Chrysaora hysoscella are each up to 30 cm in diameter and can inflict stings that may be severe and painful. Seeing no rocks but nine football sized jellyfish in two minutes, we thought better of swimming, changed plan and headed straight into port.

Sciacca to Syracuse. Sunday 8th – Thursday 12th August. 145 miles.

In the late summer of the sixth year of the second Punic war, the epic struggle between the Italian city of Rome and the African city of Carthage was balanced on the knife edge of fate. Hannibal, the Carthaginian general, having annihilated a number of Roman armies sent to halt him, had crossed the alps, marched the length of Italy and was campaigning strongly in the south. The Romans were straining to hold off his allies and were especially keen to subdue the Greek city of Syracuse which held the key both to Hannibal’s supply lines from Africa and their own intentions to re-conquer Sicily.

Archeology confirms human settlements on Ortiga in the 14th century BC. The island, barely one km north to south and 500 metres across, is separated from the Sicilian mainland by a narrow bridged waterway, enjoys natural spring water and still guards the entrance to a large, well protected bay. Greeks from Corinth understood the trade and military potential, founded Syracuse in 734 BC and colonised the surrounding mainland. It grew to the largest fortified city in Magna Grecia with half a million inhabitants and a great fleet. After victories against the Carthaginians in 489 BC and the Etruscans in 474 BC, Syracuse was seen by Athens as competing for Mediterranean supremacy in the Greek world. In 413 BC an Athenian fleet attacked, but was locked into the bay by the Syracusan vessels of war and bombarded from both ship and shore. Athenian survivors were imprisoned in a local quarry.

After further battles with her African rival in the early 3rd century , Syracuse formed an alliance with Carthage that guaranteed a period of stability. Syracuse formed a natural trading port between the Mediterranean east and west, and also a favoured stopover between Italy and Africa. In 214 BC when the defining regional political issue was the rivalry between Carthage, the established power and Rome, the challenger, Syracuse was key.

M. Claudius Marcellus a hero-warrior of the old Roman school, was armed with three legions of perhaps 25,000 men for overland assault and a fleet of 100 warships. He was confident of breaching the walls of Syracuse. Livy takes up the story: “Against this naval equipment, Archimedes had lined the walls with artillery of various sizes. Ships lying offshore were bombarded with a regular discharge of stones of great weight. The nearer vessels were attacked with lighter but much more frequent missiles.” Plutarch recounts Archimedes’ devices: “Huge beams were suddenly projected from the walls, right over the ships, which could then be sunk by great weights released from on high. Other ships were grabbed at the prow by iron claws or beaks, like those of cranes, winched up into the air, then dropped stern first into the depths. Others again were spun round and round by means of machinery inside the city and dashed on the steep cliffs….Frequently, a ship would be lifted into mid-air, and whirled hither and thither…until its crew had been thrown out in all directions.”

Marcellus recognized a superior adversary. “Let us stop fighting this geometrical giant.” The assault was abandoned and the city blockaded under siege for two years. Moeriscus, one of the three prefects of Achradina, the fortified mainland outer city of Syracuse, turned traitor to save his skin, opened the gate and allowed Marcellus to enter and plunder. Troops were under order to take Archimedes alive. Plutarch again: “Archimedes was on his own, working out some problem…not aware of the Roman’s incursion. Suddenly a soldier came upon him with drawn sword, and ordered him to Marcellus. Archimedes refused until he had finished his problem…Whereupon the soldier flew into a rage and despatched him.”

Davies reflects on what might have happened if Moeriscus had not opened the gate. “If Syracuse had resisted the Romans as it had once resisted the Athenians; if Hannibal had destroyed Rome as Rome would soon destroy Carthage; if, as a result, the Greek world had fused with Carthage, then history would have been rather different.”

We sailed three days to Syracuse, swimming at anchor on Sunday evening under the lighthouse at Licata, and anchoring among the fishing fleet in Porto Palo on the Southern tip of Sicily on Monday. By mid-afternoon Tuesday, Castello Maniace the fortified southern tip of Ortiga appeared from behind Cap Murro di Porco. The walls and buildings of Ortiga protect the harbour so well that mooring off the Ortigan quayside facing into Grand Harbour appeared unbearably airless in the heat. Instead we anchored and swam in the bay, launched our dinghy, planned our own amphibious assault and slept the night on deck.

In two days we walked the narrow streets of Ortiga several times, bought slices of pizza from a take-away overlooking the fountain of Diana in Piazza Archimedes and ate it sitting in the shade between the columns of the Temple of Athena, now incorporated into the Duomo. We saw relics from the bronze-age to Greek times in the air-conditioned luxury of the Archaeological museum, Sicilian medieval art in Palazzo Bellomo, the temple of Apollo and swans swimming around the Arethusan spring. We provisioned the boat, fixed the air leak in the fuel system, fixed the depth sounder and spent hours swimming in the bay.

Syracuse to Catania. Friday 13th – Saturday 14th August. 35 miles.

At 3,320 metres Etna is the largest active volcano in Europe. But dating back just 600,000 years, it is young. In 1669, lava destroyed 7 villages, covered a 15 sq. km area and flowed 1 km into the sea, destroying the regional port city of Catania. The 1928 eruption destroyed Mascali. Lava flow in 1971 destroyed the Astrophysics observatory, the upper cable car station and several ski lifts. An explosion and lava in July and August 2001 again destroyed the cable car station and 4 ski lifts and the villages of Nicolosi and Belpasso were only saved by dykes constructed to divert the lava flow. Between October 2002 and January 2003 molten lava at 1,100 degrees C from a smaller crater at Rifuge Torre di Filosofo at 2,940 metres destroyed the mountain refuge and gas explosions killed 5 people. The tourist guide perversely celebrates the increased tourist interest since this most recent activity.

Nick, at Circulo Nautico Nic, one of four marinas in Catania, speaks four languages, including proficient German after several years working as a machinist in Kassel. Nick directed us that to reach Etna required a 30 minute walk to the bus station, the 8:15 bus to Rifuge Sapienza at 1,900 metres, a cable car to Rifuge Montagnola at 2,600 metres, a four wheel drive “Jeep” over the lava to Rifuge Filosofo at 2,942 metres and a guided two hour hike to the summit if wind and weather permitted.

The cool wind was dangerous as we climbed down from the jeeps with black dust being blown from the grey moonscape comprising clinkers and rocks from walnut size upwards. The guides refused the summit ascent but took shorter tours around the crater which had erupted 15 months earlier. Sulphur gas and steam emerged from the core, now cooled to 600 degrees. By kicking away the surface clinkers, rocks could be reached that were hot to hold. Sulphur, Copper, Iron and other minerals gave bright and varied colours to the lumps of lava, yellow, green, red and white. We filled a small rucksack. The remains of the mountain refuge could be seen emerging from under an overhang of grey. We shared drinks, sandwiches, photo shoots and discussions with Sam, an Indian forensic psychiatrist working in London and marvelled at the powerful furnace beneath our feet.

Catania, Sicily to Cetraro, Calabria. Sunday August 15th – Wednesday 18th. 140 miles.

“Thus we sailed up the straits (of Messina), wailing in terror, for on the one side we had Scylla, and on the other the awesome Charybdis sucked down the salt water in her dreadful way. When she vomited it up, she was stirred to her depths and seethed over like a cauldron on a blazing fire; and the spray she flung up rained down on the tops of the crags on either side. But when she swallowed the salt water down, the whole interior of her vortex was exposed, the rocks re-echoed to her fearful roar, and the dark blue sands of the sea-bed were exposed.

My men turned pale with terror; and now, while all eyes were on Charybdis as the quarter from which we looked for disaster, Scylla snatched out of my ship the six strongest and ablest men. Glancing towards my ship, looking for my comrades, I saw their arms and legs dangling high in the air above my head. “Odysseus!” they called out to me in their anguish. But it was the last time they used my name.” Homer.

In November 1943, a Junkers aircraft of the German Luftwaffe, flying south from its French Mediterranean base, having taken part in exercises to withdraw remnants of the defeated Afrika Korps, encountered allied warplanes. Following success in the North Africa campaign, the allies had moved north across the straits of Sicily in July, quickly taken the island and crossed to Calabria on the Italian heel in September.

An American fighter came directly out of the sun, unseen by the Junkers crew who were hit and forced to ditch in the warm waters of the Messina straits. My father succeeded in dragging his two crew members out of the water, and after being blown south in a liferaft by wind and tide for several hours, the final phase of their war was spent as POWs in enemy hands, an adventure that was to conclude with the first Altwasser arriving in England.

With a new moon heralding the strongest spring tides, we cross-checked three tables to confirm our plan to pass through the narrows at the head of the straits, past Scylla and Charybdis, at slack tide.

Anchored off Taormina on Sunday evening we invited Joan and Peter of Asland Sentinel on board to confirm once more our plans, but they were heading to Greece, not north through the straits. Conversation was strained by the noise of a helicopter filling a great bucket with sea water and dowsing the burning trees in the rocky cliffs below Taormina. Conversation was further interrupted by a small motor boat that had slipped anchor, been blown out of the protected inshore shallows and but for getting tangled round our own anchor chain would have drifted off to Malta. Signor Capitano, who we suspect was engrossed in his own weekend entanglements below decks, was clearly embarrassed when he emerged to find four British sailors trying to take control of his vessel at arms length.

The wind in the straits varied from nothing to 25 knots and back to nothing in less time than is needed to adjust sails. The tide flowed north at three knots when we calculated it should still just be flowing south, and an hour later flowed south at three knots when we calculated it should be starting to turn north. So much for tide tables. But the biggest danger to boats in the straits today are the ferries of which we never saw less than three in transit at any one time.

Monday night in the fishing harbour at Bagnara Calabra allowed us to meet Sandy and Mervin of Benita, named, as Sandy explained, because they feel “blessed” to sail her. This contraflow encounter enabled an exchange of valuable harbour information. Also, having seen only at a distance, the specialist Swordfish boats of the straits, we were able to view them close up at the quayside. A lookout position, some sixty feet above deck is reached via a steel gantry constructed like a builders crane. A telescopic bowsprit, of similar construction allows the harpoonist to extend his reach 50 feet ahead of the boat and creep up on the unsuspecting fish.

We swam at anchor off the beach at Tropea, planning to wait until the sun was cooler before entering the windless harbour. However, by the time we tried for a berth, the harbour was full and together with seven other yachts, we anchored in the calm waters outside, ate Sardinian pasta, drank Spanish wine and watched the sun set over Stromboli and the other active volcanic Aolian islands to the north of Sicily.

The trip to Cetraro was hot and windless, we burned hydrocarbons and looked forward to better winds when visitors arrive. Ben comes aboard for three weeks from August 24th with two friends alternating. Ruth joins us for a few days from August 30th between Naples and Rome, and Lex and Mary join us in October between Pisa and Genoa. We thank Ryanair for so many routes to Italy.